BETH HAIM JEWISH CEMETERY | A BAROQUE VISUAL FEAST

About a 40-minute bike ride away from Amsterdam Centraal, in the town of Oudekerk aan de Amstel, lies Beth Haim cemetery. As the oldest Jewish cemetery in the Netherlands, Beth Haim, meaning ‘house of life’, has Dutch national heritage status for its cultural and symbolic significance. It’s also a visual treat of a cemetery for those of you who are into this kind of thing.

In the beginning...

Prior to the 16th century, there were very few Jewish settlers across what is now the Netherlands. The Dutch Jewish ‘community’ consisted of only small, scattered outposts or individual families. It was the religious persecution of the Spanish Inquisition that led to many Sephardic Jews leaving the Iberian peninsula (Portugal and Spain) for more hospitable territories across Europe. While the Dutch had allowed Jewish families to trade and settle in cities like Amsterdam, this tolerance did not extend to the necessary municipal support towards long-term community building. One of the hurdles the Sephardic Jews faced was push back against their request for a religious burial ground within Amsterdam’s city limits. In a move against this refusal, the community rallied together to purchase a four-acre plot in Oudekerk (about 10km from Amsterdam) to establish their own cemetery. While the Oudekerk villagers were openly dismayed by the plan, the Dutch authorities eventually conceded to the demand for the new burial ground. Sitting at the confluence of the two rivers Bullewijk and Amstel, the land was finally consecrated and the first Dutch Jewish cemetery was opened in 1614.

The Dearly Departed

Beth Haim became the final resting place for both the common folk and some of the celebrated Jewish men and women of the age. The demand for burial plots grew rapidly and the site required an extension into neighbouring land by the end of the century. Today, Beth Haim holds more than 28,000 graves. Samuel Sarphati, the Dutch physician and Amsterdam city planner whose name can be seen on landmarks across the capital, was buried at Beth Haim in 1866. Among the famous-adjacent in Beth Haim you’ll also find a 17th century rabbi and friend to Rembrandt van Rijn, Maria de Medici’s personal physician and the Dutch philosopher Spinoza’s mother and father.

Another well known resident of the cemetery is a man known as Elieser. His grave is alleged to be the only named resting place of a liberated slave and Black Jew in Western Europe. He was buried in 1629 and is one of around 40 more unnamed Black jews who were buried in Beth Haim up until the year 1716. This conversion to Judaism was a condition of their freedom under halakhah (Jewish law) and not exactly a consensual opt-in kind of situation. According to the Asser Institute:

Even though the practice of slavery was illegal in the Netherlands, Portuguese Jews called them ‘servants.’ According to halakhah [Jewish law], a slave owned by a Jew had to undergo a ritual at the beginning and the end of his or her service. This ritual included circumcision [for men] and a ritual bath [men and women]. This permitted Jews to have slaves for a period of twelve months, after which the slave became a full-fledged Jew. However, if the slave did not voluntarily embrace the Jewish faith, the owner was obligated to sell his or her slave to non-Jews. One way to circumvent this was by giving the slave to another Jew as a gift, before the expiration of the twelve months.

In 2013, the village of Oudekerk memorialised Elieser with a statue by the Surinamese artist Erwin de Vries. ‘Elieser Day’ held each June sees dozens of Dutch-Surinamese pilgrims visiting the statue to reflect on this figurative ancestor for the community. One of the pilgrims, Sergio Berrenstein, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in 2020 that:

My knowledge of my family doesn’t go further back than my great-grandparents. For me and for many others in the Black community, Elieser’s grave is as close as we can get to them.

Beeld van Elieser beklad met oranje verf. Image source: Het Parool

Situated next to the entrance to Beth Haim, the statue was unfortunately vandalised in 2020 as a backlash to the #blacklivesmatter movement that swept the globe. The statue was defaced with the red spray painted letters WLM (White Lives Matter) not long after Elieser Day. Oudekerk’s mayor was quick to repair the damage and their alderman denounced the action as ‘disgusting, infuriating and cowardly.' While this sentiment represents a vocal minority, it brings us full circle to the outrage that almost stopped the establishment of Beth Haim in the first place. Also at Beth Haim you will find a small memorial to victims of the Holocaust. Here we have yet another reason why cemeteries are important and so darned interesting. The complex, overlapping stories and people we can explore through these spaces remain highly relevant even long after they’re gone.

A Visual Feast

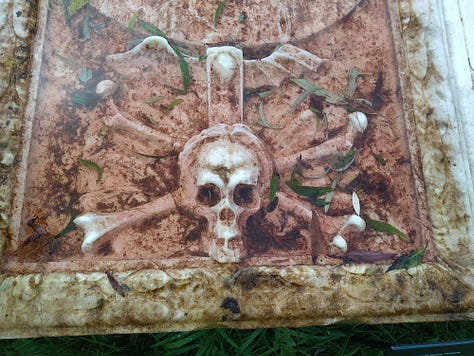

Over the intervening centuries many gravestones have been buried in the swampy Dutch soil, lost in overgrown foliage or damaged, but those that remain are quite extraordinary. They show inscriptions in Portuguese, Dutch, Latin and Hebrew, and feature loud, eccentric Baroque carvings that resemble Catholic headstones more than Jewish ones. The Catholic iconography in Beth Haim is reflected through symbols like skulls, biblical scenes, lambs and cherubs. The Baroque style of art and decoration is characterised by flamboyant detail, sharp contrasts, and bold, grand and surprising statement pieces intended to shock and/ or amuse. It isn’t for everyone and is often relegated to the realm of the kitsch by contemporary audiences. However you might feel about them, these visually energetic memorials give a vibrant nod to the lives of those interred and the era that they lived through.

Meandering through the graves is a morbidly fun excursion for any time of year, but seeing the gravestones partially flooded on a rainy day adds to the gloomy, sepulchral vibe. How clued up are you on your Westen gravestone symbolism? Let’s take a dive into a few of the most common ones seen at Beth Haim.

Winged hourglasses

The winged hourglass alludes to the fleeting nature of time. Acting as a memento mori, it reminds us that we don’t know what time we have, so we’d better use it well. A remarkable customisation at Beth Haim is that many of these winged hourglasses feature both a pigeon wing and a bat wing. The pigeon wing is meant to symbolise day (good) and the bat wing symbolises night (evil). This conflict between the forces of good and evil is a hallmark of Christian and Jewish traditions alike.

Lamb

The lamb represents innocence and sacrifice and is often featured on the graves of children. In the Christian tradition, the lamb is linked to the myth of Jesus Christ, but this symbol was also used long before the advent of Christianity by the ancient Egyptians.On a gravestone in Beth Haim the lamb is featured in a scene from the story of Abraham. Abraham is about to sacrifice his son Isaac at an altar, but he receives a message from God to stop just in time.

Crown and Lion

The crown and the lion symbolise royalty. In rural North Holland, these figures are more symbolic than denoting a familial lineage. They show high honour and respect to the deceased as might be given to members of a royal family

Winged skull/ Cherub

Winged skulls allude to life after death. Once the physical body is shed, the spirit can move on. In some parts of the world, the winged skull was replaced by the less morbid symbol of a winged cherub - a youthful symbol of rebirth. Beth Haim features a few cherubs crying emphatically over the graves they are guarding. A crying cherub symbolises deep grief and sorrow, ultimately personifying the loss and love of those left behind.

Laurel wreath

The laurel wreath is a symbol of triumph. On a grave, it represents triumph over death through immortality.

Torch

Shown with the flame pointing upwards, a lit torch also represents immortality. But shown inversely, the torch dramatically symbolises an eternal flame that can survive against the odds, referring to death and the transition from one state of being to another.

Scythe

Across Europe, the scythe has been associated with death since the middle ages. In the pre-Industrial era, these sharp, slicing implements would have been commonly seen in day-to-day life, but modern humans only tend to know them for their symbolic significance. Scythes (and sickles) draw a metaphorical link between reaping crops and a deathly figure reaping lives.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments. 💀

Sources

Bethhaim.nl. https://www.bethhaim.nl/english/

Jewish cemetery Beth Haim at Ouderkerk aan de Amstel. Lydia Hagoort, for Dutchjewry.nl. http://www.dutchjewry.org/portuguese_israelite_cemetery/about_portuguese_israelite_cemetery.shtml

NETHERLANDS: BETH HAIM, A 17TH CENTURY PORTUGUESE-JEWISH CEMETERY NEAR AMSTERDAM. Minor Sights. http://www.minorsights.com/2014/08/netherlands-beth-haim.html

Cemetery Review #10 – Beth Haim “House of Life” – Ouderkerk aan de Amstel – The Netherlands. Claudia Crobatia, for A Course in Dying. https://acourseindying.com/cemetery-review-10-beth-haim-house-of-life-ouderkerk-aan-de-amstel-the-netherlands/

Jewish Cemetery in Sarajevo. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6334/

African blacks and Mulattos in the 17th-Century Amsterdam Portuguese Jewish community. Yehonatan Elazar-DeMota, for the Asser Institute. https://www.asser.nl/global-city/news-and-events/african-blacks-and-mulattos-in-the-17th-century-amsterdam-portuguese-jewish-community/

Monumenten Ouder-Amstel - Elieser. Historisch Amstelland. https://www.historischamstelland.nl/ontdekken/monumenten-ouder-amstel/kunst/elieser

Standbeeld Elieser in Ouderkerk beklad met letters 'WLM'. Amstelveenz.nl. https://www.amstelveenz.nl/nieuws/standbeeld-elieser-in-ouderkerk-beklad-met-letters-wlm.html

Beeld van Elieser beklad met oranje verf. Het Parool. https://www.parool.nl/amsterdam/beeld-van-elieser-beklad-met-oranje-verf~b120626c/

A Dutch Jewish cemetery has become a Black pilgrimage site. Cnaan Lipshiz, for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. https://www.jta.org/2021/01/20/global/a-dutch-jewish-cemetery-has-become-a-black-pilgrimage-site

The bat, a funerary fascination. Totzover.nl. https://www.totzover.nl/english/bats-funerary-fascination/

Alpha to Omega: An Introductory Field Guide to Decoding Cemetery Symbols. Kurt Kohlstedt, for 99% Invisible. https://99percentinvisible.org/article/alpha-omega-introductory-field-guide-decoding-cemetery-symbols/

The Language of Death: 15 Gravestone Symbols Explained. SA Rogers, for Web Urbanist. https://weburbanist.com/2015/10/28/the-language-of-death-15-gravestone-symbols-explained/

Jewish Gravestone Symbols. Bloodandfrogs.com. https://bloodandfrogs.com/2011/04/jewish-gravestone-symbols.html

Cemetery symbols and the art of death. Frazer Consultants. https://web.frazerconsultants.com/2016/07/cemetery-symbols-and-the-art-of-death/