GETTING TO KNOW CAPE TOWN'S 'CIRCLE OF TOMBS'

The cult of saints is a phenomenon that spans many modern and ancient religions. In Catholicism and Islam, saints are individuals that are distinguished during their lifetime for their good deeds, high degree of faith, piety, and/ or spiritual influence in their community, as well as any miracles that can be attributed to them. Long after their death, these saints are venerated and their graves become sites of pilgrimage for believers seeking their guidance and blessings.

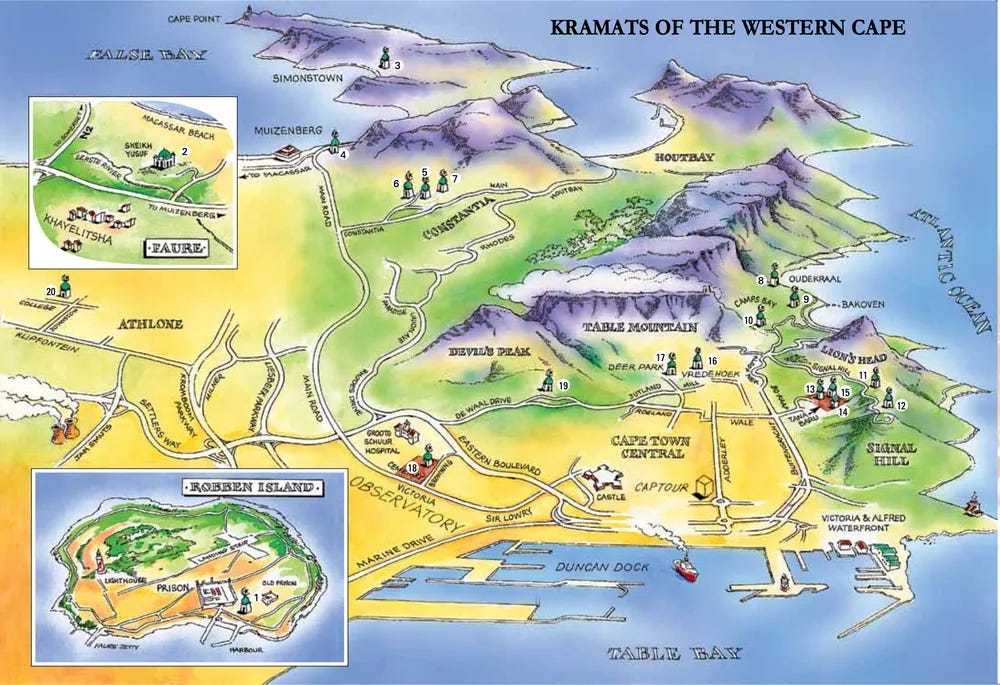

Cape Town has more than thirty Muslim shrines (kramats or mazaars) dotted across the peninsula. The shrines mark grave sites commemorating historical Auliyah (‘Beloved of Allah’) who were brought as political exiles to South Africa by the Dutch. Despite accounting for less than 2% of South Africa’s total population, the country’s Muslims have built a strong community and cultural identity with a legacy of displacement, defiance, and religious devotion. Although well known to community members who visit regularly and uphold the memory of the saints, the kramats are not widely known across other South African communities. Mogamat Kamedien, historian for the Cape Mazaar Society describes the kramats as “trans-oceanic storehouses of memory.” The circle of tombs are built archives and keepers of oral history that sustain the link between Capetonians of Southeast Asian descent and “their lost cousins on the other side of the Indian Ocean.”

Building a legacy

The placement of Cape Town’s kramats form what is referred to colloquially as the circle of tombs. This ring is rumoured to protect the region from earthquakes and other natural disasters. Kamedien explains that:

As long as this circle of kramats is here, there will be a circle of protection for Cape Town. The kramats are broader than the Muslim community, it’s for everyone in Cape Town who recognises this sacred geography.

The arrival of Islam to southern Africa is a direct (yet inadvertent) side effect of Dutch colonialism. From 1652, Jan van Riebeeck overtook the Cape and set up a refreshment station for ships going to and from the East. By this point, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had established a strong naval presence across multiple territories, including modern day India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Indonesia. Regional rulers, their advisors, and high-ranking followers fought against European colonial rule, but in the end, many were defeated, captured, and shipped to the Cape. Fearing that their execution risked turning them into martyrs, these men, along with enslaved people and convicts, were instead banished to the Cape of Good Hope by their captors.

These high-profile exiles brought their defiance and religious devotion with them, and established an enduring following in the land they would call home for the rest of their natural lives. Islam spread rapidly during the 18th century through the conversion of many slaves and free labourers seeking the social and spiritual benefits of the religion. In the 1790s, under the British Governor General Craig, the Muslim community were permitted to establish their first mosque, the Auwal Masjid that still stands in the colourful Cape Town suburb of the Bo-Kaap. In 1805, Tana Baru cemetery was established for Muslim burials, with a small section of the plot reserved for Chinese burials as well. With these landmarks, they had set down roots that would anchor the community even 300 years later.

National Heritage Status

In December 2021, ten kramats across Cape Town were declared national heritage sites by the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), after years of campaigning led by the Cape Mazaar Society and Vidamemoria Heritage Consultants. This denomination has been widely celebrated and will support the upkeep and protection of the sites going forward.

While all of the kramats have their own compelling histories, here is a quick dip into a few of the most prominent in Cape Town CBD and the Southern Suburbs.

The kramats of Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah and Sayed Mahmud

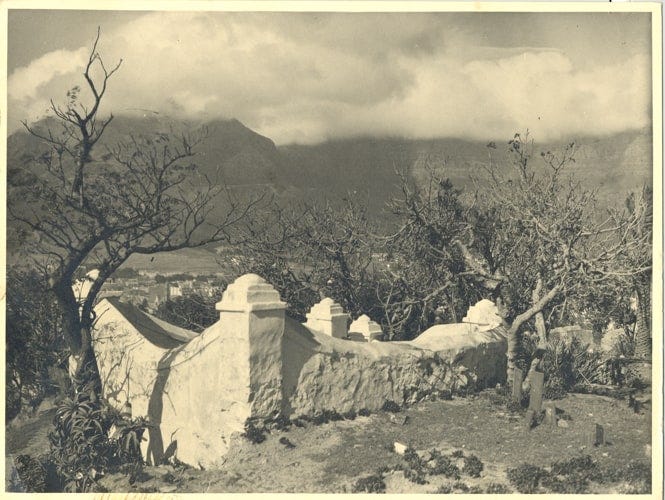

It is only from the start of the 20th century that the shrines have been marked by permanent structures. Originally, the saints tended to be buried in well secluded spots, marked by paths of stones or tied bits of cloth for pilgrims to follow into the mountains or forests. Eventually, wooden shacks were erected at some of the sites as precursors to the brick and mortar buildings of today.

In 1667, Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah (the last Malaccan Sultan) and Sayed Mahmud and Sayed Abduraghman Motura (his advisors) were the first to be brought to Cape Town. An inscription on a stone tablet at the kramat of Sayed Mahmud in Constantia describes their banishment from modern-day Jakarta (Indonesia) as follows:

On 24 January 1667, the ship the Polsbroek left Batavia and arrived here on 13 May 1668 with three political prisoners in chains. Malays of the West Coast of Sumatra, who were banished to the Cape until further orders on the understanding that they would eventually be released. They were rulers ‘Orang Cayen’, men of wealth and influence. Great care had to be taken that they were not left at large as they were likely to do injury to the Company. Two were sent to the Company’s forest and one to Robben Island.

Sheikh Abdurahman Matebe Shah is buried on Klein Constantia farm next to a river where he would regularly meditate. The Cape Mazaar Society who constructed the permanent shrine structure described the site’s potent atmosphere as follows:

One felt as if one was in the living presence of history, standing in a sacred spot filled with a spiritualism. The place had a serene atmosphere, with the tranquility sweetly broken by the running water and the chirping of birds. The cramped little shack, with its small window and grave inside was a wonderful place.

In close proximity, the shrine to Sayed Mahmud is tucked away on Summit Way in Constantia and nestled in a lush garden. Also referred to as Islam Hill, the gardens and shrine itself are a space for peaceful contemplation to any and all visitors, according to the caretaker, Faizel Bassier. The original shrine was commissioned in 1927 by the philanthropist Haji Sullaiman Shahmohammed and designed by Franklin Kaye Kendall, a partner of the architect Sir Herbert Baker. By the early 2000s, the site had fallen into disrepair. In 2018, a new shrine and additional structures on the property had been designed and built by the architect Gabriel ‘Gawie’ Fagan. The garden layout was overseen by his wife, Gwen Fagan. The garden’s design gives a nod to the resplendent grounds of the Alhambra castle and palace complex in Granada.

In 2018, unknown arsonists attacked the Islam Hill kramat. The interior of the shrine was set alight, damaging the carpet and blackening the walls. Storage cupboards were also damaged, but copies of the Qur’an stored within were spared any harm. Bassier, who put out the fire, describes this as “karama, a miracle” that he attributes to the intervention of the saint.

Kramat of Sheikh Yusuf, Macassar

Arguably the best known saint in the region is Sheikh Yusuf. After being detained in both Batavia and Ceylon for many years, he arrived at the Cape in 1694, along with two wives, his children and a large party of friends and supporters. During their journey, it is said that their ship ran out of its fresh water stores. Sheikh Yusuf performed a miracle by turning the seawater around their ship to freshwater by dipping his foot into it. While some have speculated that this could be that they had sailed into a freshwater tributary off the coast of Natal, many followers of the saint continue to recount this story as proof of his mystical influence.

Sheikh Yusuf settled and died at Zandvliet (Macassar), an area on the outskirts of Cape Town and set away from the growing settlement at Stellenbosch. The authorities believed that this remote outpost would diminish his influence, but over the years he attracted runaway slaves and worked with 12 imams to carry out Islamic religious instruction and services in secret.

Over a short time, he founded a stable and growing community built on the teachings of Islam and social cohesion. When he died in 1699, he was buried in Zandvliet. Today, the area is commonly considered to be the true birthplace of the faith in South Africa.

Kramat of Sheikh Mohamed Hassen Ghailbie Shah, Signal Hill

Perched between Lion’s Head and Signal Hill is the Kramat of Sheikh Mohamed Hassen Ghaibie Shah al Qadri. This shrine has resplendent, unobstructed views of Table Mountain, Robben Island and the Atlantic Ocean, and is dedicated to one of Sheikh Yusuf’s early followers.

Also on Signal Hill are the graves of Tuan Kaape-ti-low, Tuan Nur Ghiri Bawa (also known as Tuan Galieb), Tuan Sayed Sulaiman and Tuan Sayed Osman. Tuan Kaape-ti-low is said to have arrived in South Africa in the late 1600’s as an exiled military general from Indonesia. His grave is marked by a low stone wall and metal gate. It sits on what is now also a local scout campsite (Appleton). Unfortunately, there is very little known about the lives of the other men.

Kramat of Sheikh Noorul Mubeen, Oudekraal

Sheikh Noorul Mubeen is buried along the Atlantic Seaboard, at Oudekraal. To reach his grave, pilgrims walk up a concrete set of stairs that start at Victoria Road and meander into the forested area below the Twelve Apostles mountain range.

Sheikh Noorul Mubeen arrived in Cape Town in 1716 and was initially held at Robben Island. It is said that he escaped his imprisonment soon after and settled in the mountains. Slaves would travel to receive his teachings under the cover of darkness. One of the stories relating his daring escape claims that he swam from Robben Island directly to the mainland. In this telling, he was found by slave fishermen who nursed him back to health. Another version claims that he simply walked across the water to the mainland, invoking his holy and mystical powers to do so. Today it is claimed that his shrine is visited by a spirit riding a white horse across the water from Robben Island.

Kramat of Tuan Guru

The Auwal Masjid’s first Imam was Abdullah IbnQadhu Abdus Salaam, also known as Tuan Guru. He was an exiled prince from Tidore, Indonesia, who had been imprisoned on Robben Island for a time. For its part, Robben Island was a notorious leper colony from 1846 to 1931. It also housed a maximum security prison that held some of South Africa’s most high profile political prisoners of the 20th century, including Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe among others.

Tuan Guru’s kramat is set in Tana Baru cemetery. During his lifetime, he led the community in worship and established a religious school. At the time, it was not uncommon for free Black Muslims to own slaves like their White Christian counterparts. With influence from Tuan Guru, strict rules were laid down in the Muslim community restricting members from owning or trading in slaves. Achmat van Bengalen (a contemporary leader in the Muslim community) described these rules as:

No Mohametan can or ought to sell a Mahometan as a slave. If he buys a slave from a Christian and that slave becomes a Mahometant, he is entitled to sit down as an equal in the family, and cannot be slaved afterwards. He is allowed to earn the means of redeeming his freedom if he chooses, or remain connected with the family of the original owner.

In 2015, the Capetonian artist Thania Petersen, a descendent of Tuan Guru, mounted a photo exhibition at AVA Gallery where she reimagines the life of a royal she might have had if her ancestor hadn’t been torn from Indonesia by the Dutch. Posing in sumptuous attire and set in outdoor spaces across the city, her photographs paint an alternative visual and historical narrative that asserts herself as a regal keeper of her own destiny and not simply a footnote to colonialism.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments. 💀

A note on visiting the sites

As your intrepid and ever curious host, I set off to visit multiple kramats on a hot, sunny day in November 2022. The caretakers on site are welcoming and knowledgeable about the history and contemporary significance of the properties. They confirmed that non-Muslims are welcome to visit the shrines and enjoy the tranquil, natural surroundings. When visiting, shoes should be removed when entering the building and silence should be observed. Visitors should stand or sit facing the grave within the shrine structure. It is not okay to lean against, rest on or sit on the grave. Needless to say that eating and drinking in the shrine is also not permitted.

Sources

'Circle of saints': the corner of Cape Town that's a Muslim resting place. Richard Holmes, for The National - Weekend. https://www.thenationalnews.com/weekend/2022/06/10/circle-of-saints-the-corner-of-cape-town-thats-a-muslim-resting-place/

Watershed moment for Muslim community as 10 kramats in Cape Town get declared heritage sites. Rafiekah Williams, for Cape Argus. https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/watershed-moment-for-muslim-community-as-10-kramats-in-cape-town-get-declared-heritage-sites-384a2ad4-45c4-4b9b-bbe7-b5586eb76fde

Nod to Circle of Tombs’ heritage value. Nettalie Viljoen, for People’s Post. https://www.news24.com/news24/community-newspaper/peoples-post/nod-to-circle-of-tombs-heritage-value-20201130

Circle of Kramat's, Cape Town. South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/circle-kramats-cape-town

Guide to the Kramats of the Western Cape. Published by the Cape Mazaar (Kramat) Society. Editor: Mansoor Jaffer. 2010 Edition. http://capemazaarsociety.com/book.pdf

Proposal for National Heritage Site Declaration: The first ten Kramats in the Circle of Tombs Serial Nomination, Western Cape. South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA). https://sahris.sahra.org.za/sites/default/files/additionaldocs/Declaration%20Submission%20-%20Kramats.pdf

Sunni Islam, Rituals and Worship, Sacred Space. Patheos.com. https://www.patheos.com/library/sunni-islam/ritual-worship-devotion-symbolism/sacred-space

Cape Malay: a South African Muslim identity borne out of colonialism. Yaseen Kader, for gal-dem.com. https://gal-dem.com/cape-malay-a-south-african-muslim-identity-born-out-of-colonialism/

Places to Visit - Kramats. Muslim Directory. http://www.muslim.co.za/tourism/placestovisit/kramats

Islam Hill Kramat. Gabriel Fagan Architects. https://www.gabrielfaganarchitects.com/islam-hill-kramat

Heritage nod for city’s Muslim shrines. Karen Watkins, for Constantiaberg Bulletin. https://www.constantiabergbulletin.co.za/news/heritage-nod-for-citys-muslim-shrines

Kramat site torched. Karen Watkins, for Constantiaberg Bulletin. https://www.constantiabergbulletin.co.za/news/kramat-site-torched

Kramat of Sheikh Hassen Ghaibie in line for heritage status. Radio 786.co.za. https://www.radio786.co.za/kramat-of-sheikh-hassen-ghaibie-in-line-for-heritage-status/

About Islam at the Cape. The Muslim Judicial Council (SA). https://mjc.org.za/education/islam/about-islam-at-the-cape/

History of Muslims in South Africa: 1700 - 1799. Ebrahim Mahomed Mahida, for South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/history-muslims-south-africa-1700-1799-ebrahim-mahomed-mahida

Visiting the oldest extant cemetery in South Africa. SJ de Klerk, for The Heritage Portal. https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/visiting-oldest-extant-cemetery-south-africa

AUWAL MASJID 39 Dorp Street BO-KAAP. South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA). https://sahris.sahra.org.za/sites/default/files/heritagereports/2015%20Auwal%20Masjied%20background%20document.pdf

Cape Mazaar Society website. http://www.capemazaarsociety.com/

Appleton Scout Camp. Scout Wiki. https://scoutwiki.scouts.org.za/wiki/Appleton_Scout_Camp

The Leprosy Outbreak on Robben Island. David Fleminger, for Southafrica.co.za. https://southafrica.co.za/leprosy-outbreak-on-robben-island.html

I AM ROYAL - SOLO EXHIBITION 1 JANUARY - 1 DECEMBER 2015. Thania Petersen. https://www.whatiftheworld.com/exhibition/i-am-royal/