IS IT OKAY TO COLLECT HUMAN REMAINS?

The compulsion to build collections of things is a common human trait, and collections tell us quite a lot about the values and ideas of the age in which the things are collected. But are human beings just things when they die, and is it ethical to have them in a museum or university’s custody? Some may argue that ancient corpses are more appropriate than fresh ones. The impossibility of having walked past the person on the street is one way of protecting the viewer from confronting their own mortality when seeing the dead. However, in light of what we now know about world history over the last 500 years or so, the intentions and origins of many collections have been probed with some uncomfortable questions.

A brief history

Human remains refers to any part of a deceased person in any state of decomposition - from hair, bones, teeth and fingernails, to detached limbs and whole corpses. For centuries, they have been collected in many ways for a host of good and bad reasons. In this case, we’re taking a look at human remains in Western museums and university collections in the Global North and former colonies.

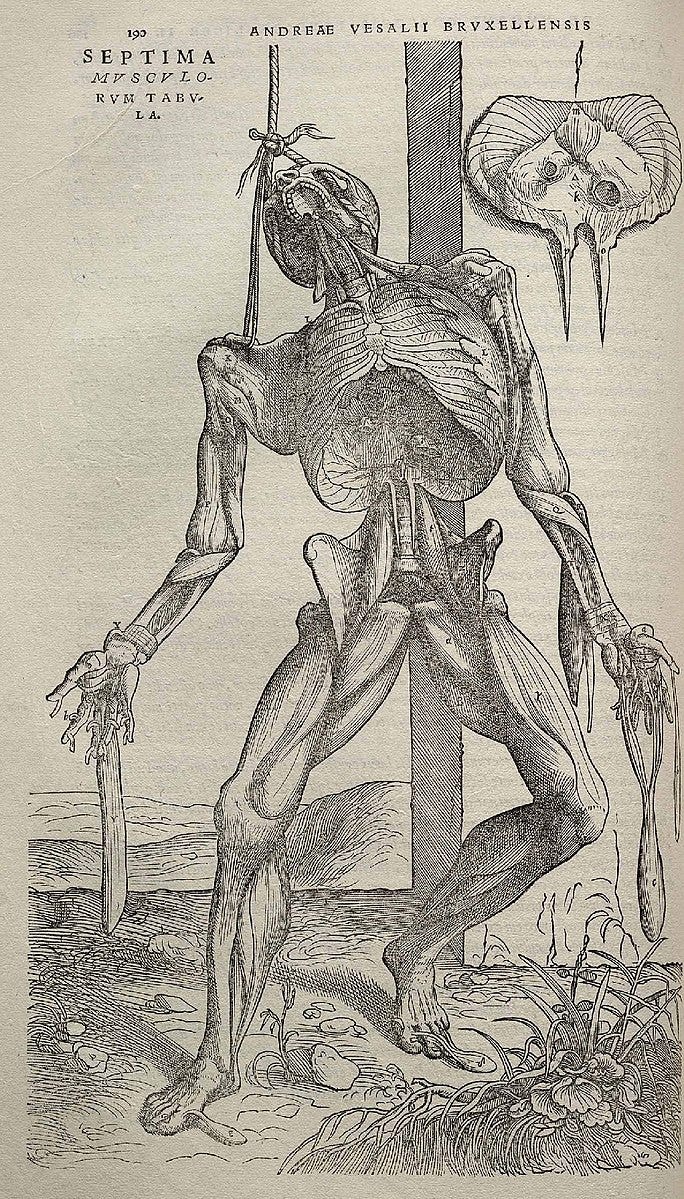

Anatomy is the study of the bodily structure of living things, and it is the oldest discipline of medicine. Dissection of corpses has been the main teaching tool for anatomy since the 3rd century B.C. in ancient Greece. After medieval times, the increased frequency of dissections was influenced by a number of factors including the establishment of medical schools and universities in major cities like Bologna and Paris, as well as favourable concessions made by the Roman Catholic church to support medical advancements. By the Renaissance (roughly 1400-1600), the Western world was as interested in the natural, theological and aesthetic qualities of the body as its scientific uses - seeing it as a potent symbol of divine creation.

Public dissections to galleries of students and sometimes members of the public were carried out using bodies of deceased criminals or other individuals from the margins of society. In some cases, human remains were procured through illegal grave robbing to feed the high demand.

The problem with a cadaver of course is that it doesn't last. The natural process of decomposition renders the body a single-use object, unless interventions are made to capture the dissected body for future reference. To this end, anatomists first flexed their artistic skills to render dissected bodies in detailed drawings for educational purposes. The practice then shifted to preservation activities, such as removing flesh to reveal dry bone structures, or turning body parts into wet specimens by placing them into jars with a chemical fixative. These specimens grew into larger collections to support research and education, and in some cases, to fulfil the public’s morbid interest in body parts. Today, it is not uncommon for anatomical collections to be open to visitors in small museum settings on university campuses.

The Western museum concept stems from the Enlightenment - an age of philosophical and intellectual advancements across the 17th and 18th centuries. Museums come in a number of flavours based on the common elements of their collection, meant to educate, titillate and entertain. Many of the world’s larger museums have collections that offer a bit of everything - from arts and culture, to natural and human history. And what you’ll see on display represents only a fraction of what is maintained behind closed doors, with the potential to be put on view in future exhibitions. In these settings, you may encounter a human skeleton, a mummified corpse or a shrunken head picked up by an anthropologist or archaeologist long before the current museum staff were even born. They are intended to show visitors the diverse life and death rituals of ancient humans. More often than not, this is done in a way that exoticises and lacks a deeper degree of justification for the museum’s possession of these objects. Anatomical specimens often also make their way into museum settings from private collections. This begs the questions: where did these remains come from, and under what circumstances were they acquired?

Where there’s smoke…

While it’s sometimes difficult to know the minute details of the practices of the middle ages, the Renaissance or the Enlightenment, it is easier to quantify the shady collection activities of the 19th and 20th centuries. Museum and university collections of human remains are used to study important things, like human evolution, embryonic development, and congenital defects and diseases. These endeavours are still considered legitimate, but any accompanying research into ‘race’ based on the study of physical anthropology and founded on principles of white racial supremacy is now widely discredited. In addition to the dark intentions of the collectors, many regions of the world also have horror stories of cruel and inhuman collection activities undertaken for Western scientific and non-scientific consumption. Southern Africa has many of its own grim tales.

In the 19th century, the Khoisan in particular were considered to be native animals of Southern Africa and not human beings. The first instance of Khoisan body parts entering international museums stems back to the early 1800s, and by 1850 it is estimated that Khoisan specimens could be found in most major European museums. In 1805, the German doctor, Hinrich Lichtenstein, wrote about acquiring a “cranium of an unknown female Khoi who had been found dead in the veld.” This detached account doesn’t provide any details about the circumstances that led to the woman’s death, instead focusing on the luck of the author to find the prized piece. It is impossible to know the further nefarious deeds that these scant, unsettling words may mask.

Most famous among these stories is the tale of Sarah 'Saartjie' Baartman (1789 - 1816) and her mistreatment in life and in death. A Khoisan woman raised as a slave in the Cape, she was taken to London in 1810 to be exhibited as a sideshow attraction for the public to ogle at her appearance. Saartjie was also taken to France where the medical establishment fell over themselves to examine every intimate angle of her body. Dying at just 26 years old due to illness, she was dissected by the French naturalist and anatomist, Georges Cuvier. A cast was made of her entire body, and her skeleton, genitalia and brain were preserved. After being in the custody of a number of institutions over the next century, what remained of Saartjie was put on public exhibition in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. In 1994, President Nelson Mandela insisted that her remains be repatriated to South Africa for a dignified state burial. The request for her return was finally honoured by the French National Assembly, and she was buried in the Eastern Cape on 9 August 2002 (Women’s Day). Saartjie’s body was not used for significant research. She faced the establishment and the public’s scrutiny as a perceived freak. She was a justification for many of the racist ideologies that were percolating in the white nationalist zeitgeist over the last two centuries.

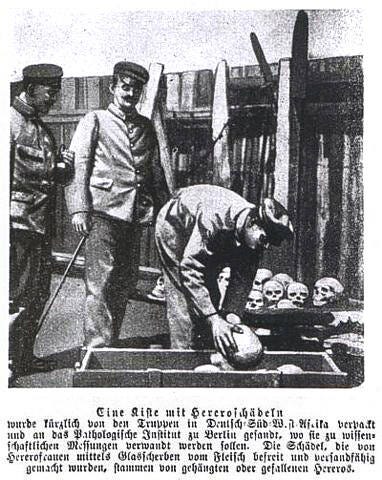

Between 1904 and 1908, the German colonial administration carried out a little-known genocide in Namibia that would foreshadow the horrors of the Holocaust in later decades. The genocide resulted in the decimation of 80% of the Ovaherero and more than half of the Nama population, as well as casualties among the San and Damara. In the concentration camp on Shark Island, Lüderitz, the bodies of deceased detainees were carved up, defleshed and shipped to Germany for study. At the time, the Namibian skulls were used for enquiries into racial superiority and little else. For most of the 20th century, Germany denied the genocide had even taken place, but in recent years, the atrocities have been officially acknowledged. Multiple institutions have also begun to repatriate skulls in their collections that stem from Namibia under German rule.

Towards ethical practices

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) sets the standards for the international museum community. Their Code of Ethics lays out a number of clauses for human remains, including the clause on acquiring new specimens:

Collections of human remains and material of sacred significance should be acquired only if they can be housed securely and cared for respectfully. This must be accomplished in a manner consistent with professional standards and the interests and beliefs of members of the community, ethnic or religious groups from which the objects originated, where these are known. (ICOM, 2018)

Unfortunately, the code stops short of expecting museums to take responsibility for the origins of their existing collections. In contrast, the UK’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport calls for museums to have a comprehensive catalogue of all human remains in their collection to be made available to the public, including the identity, date of death (or approximation), physical condition and where the remains came from.

South Africa’s museums and universities follow in these Western traditions, carrying both their strengths and weaknesses into the 21st century. Human remains held in South African museum and university collections predominantly stem from the colonial and apartheid administrations of the 20th century. Established in Cape Town in 1825, the IZIKO South African Museum is an institution dedicated to history, public education and scientific research. In 2017, it was revealed that some of the human remains in its collection came from Namibia in the 20th century, totalling more than 80 items. The individual names of the deceased are not known as the skulls and bones are categorised as ‘specimens’ and given only ethnic labels. Under the auspices of the Human Remains Management in Southern Africa project, a report was released to publicise the findings and a commitment was made by IZIKO Museums to begin the process of repatriation to Namibia. Given the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic (2020-2022), it is unclear whether this process is still ongoing.

Many South African universities have also been re-examining their collections to address any unethical collections processes in their past. These institutions include the Pretoria Bone Collection (University of Pretoria), the Raymond A. Dart Collection of Human Skeletons (University of the Witwatersrand) and the Kirsten Skeletal Collection (Stellenbosch University). These investigations have led to deaccessioning of remains without a provenance or with plausibly unethical origins, as well as an active drive towards transparency regarding current acquisition practices. Some bodies are donated to these institutions by individuals who want their remains to be used for research and educational purposes, while others tend to be anonymous, unclaimed cadavers received from state hospitals.

Cultural practices and sensitivities vary wildly when it comes to the treatment of the body after death. This is especially visible in South African contemporary society. While some may be perfectly happy to donate their bodies to science, others must be buried intact to ensure their resurrection. This raises questions around consent for the anonymous dead: are they the new frontier of the debate on ethical collection of human remains, or are they simply the new faces of an old problem?

…and beyond!

It is not unnatural to be curious or interested to view the dead, but in the modern age, there are many contextual factors to take into account. The ethics of having human remains on display are tied up in the origin and treatment of the remains in question.

Museums and universities give the appearance of being just a collection of stuff that was/ is available. In truth, they are not naturally occurring and never neutral. A whole host of biased decisions go into their creation, their ongoing collections policies and their maintenance. When encountering human remains in a museum or university setting, it is not unreasonable to expect that their modern custodians know the origins of these remains. They need to be sensitive to the expectations of the modern viewer who will question the ethics of their supply chain and original intentions. It is hugely important for these collections to remain dynamic and responsive, and for sector leaders and governments to work together to hold all parties to a high ethical standard.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments. 💀

Sources

Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era. Sanjib Kumar Ghoshcorres. 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4582158/

The Anatomical Venus. Joanna Ebenstein. 2016.

The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums & why We Need to Talk about it. Alice Procter. 2020.

The Reflection of the Collector: San and Khoi Skeletons in Museum Collections. Alan G. Morris. 1987. https://doi.org/10.2307/3887769

Inside Shark Island, Germany’s First Concentration Camp — Used Decades Before The Holocaust. Andrew Milne, for Allthatsinteresting.com. 2020. https://allthatsinteresting.com/shark-island

Colonial Repurcussions: Namibia - 115 years after the genocide of the Ovaherero and Nama. European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR). 2019. https://www.ecchr.eu/fileadmin/Publikationen/ECCHR_NAMIBIA_DS.pdf

ICOM Code of ETHICS for Museums. International Council of Museums (ICOM). 2018. https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ICOM-code-En-web.pdf

Guidance for the Care of Human Remains in Museums. UK’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). 2005. https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/DCMS-Guidance-for-the-care-of-human-remains-in-museum.pdf

The Iziko South African Museum. Iziko Museums. 2022. https://www.iziko.org.za/museums/south-african-museum/

Report on the Human Remains Management and Repatriation Workshop, 13th -14th February, 2017. Dr Jeremy Silvester, Museums Association of Namibia. https://icme.mini.icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2019/01/Report_on_the_Cape_Town_Workshop_02.17.pdf

The Pretoria Bone Collection: A 21st Century Skeletal Collection in South Africa. L’Abbé, E.N. & Krüger, G.C. & Theye, C.E.G. & Hagg, A.C. & Sapo, O. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci1030020

The History and Composition of the Raymond A. Dart Collection of Human Skeletons at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Dayal, M. & Kegley, A. & Strkalj, G. & Bidmos, M. & Kuykendall, K. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21072

Composition of the Kirsten Skeletal Collection at Stellenbosch University. Alblas, A. & Greyling, LM. & Geldenhuys, E. 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/ sajs.2018/20170198