It will be surprising to some to discover that there is an ossuary in the heart of Cape Town. Ossuaries are defined as a place or receptacle for human remains. More specifically, ossuaries are a space that bones are moved to long after burial in order to free up older burial space for new bodies. The Prestwich Memorial was built to house the remains of about 2,000 anonymous individuals from a forgotten, informal burial ground uncovered during the development of the Rockwell hotel on Prestwich Street in 2003. At the time, this discovery sparked controversial disputes between government, academic institutions, civil society and the commercial developers. Ultimately, the memorial was built a few blocks away in 2008 in an attempt to placate all parties and to give the remains a permanent resting place. But 15 years after its opening, the Prestwich Memorial remains a virtually anonymous plot on the South African heritage landscape.

PRESTWICH MEMORIAL

Prestwich Memorial is located on the corner of Somerset Road and Buitengracht Street. It bears the distinction of being the only ossuary in South Africa. The site selected for the memorial is in the city’s former District One. This plot used to hold the Dutch Reformed Church cemetery and a portion of the old cemetery wall remains (front left of the building if you approach it from the Cape Town Fanwalk side). The exterior of the building is clad in Malmesbury shale stone, quarried from the land that is now the V&A Waterfront, and is intended to mimic the style of old cemetery walls. The building can be opened up on both sides to allow visitors to pass straight through it, almost like a gateway to the suburbs of the Waterkant and Green Point. The property is free to access, with floor space dedicated to informational panels and pull up banners.*

The discovery and excavation of human remains in 2003 was not the first for Cape Town and is not expected to be the last. The City of Cape Town identifies these remains as members of the city’s “17th and 18th century underclasses – the indigenous people, the poor, slaves and victims of shipwrecks.” They were buried outside of the city’s formal burial grounds due to their social status and lack of affiliation to the established religious institutions of the time. The city’s formal burials would have taken place in the Dutch Reformed burial ground (the first at the Cape), Islamic burial ground (Tana Baru, est. 1805), Anglican burial ground (est. 1832), Lutheran burial ground (est. 1833) and Catholic burial ground (est. 1840).

Informal burial grounds sprang up outside the city limits at the time, in land that has now been subsumed by the modern metropolitan areas. Robert Semple, a merchant, wrote in 1805 of an evening walk along the coast at Green Point:

[Addressing his friend, Charles] …“Tread lightly, tread lightly, my friend, we now approach a region sacred to silence and deep repose. These black and white stones are memorials of the dead - and of the neglected dead. Yonder is the slaves’ burying ground.” To this, my friend answered not a word: at the mention of the slaves’ burying ground, he stopped suddenly, and then as quickly walked on. We soon reached the spot, where it was plain, from the number of little hillocks, and the disposition of the stones, that it was indeed a burying ground: a mournful silence reigned around us: Table Bay was hushed, or at most, a faint murmur was heard upon its shores - the moon was muffled up in the spreading clouds, and we remained as if riveted to the earth in silent meditation, when we heard the sobbings of someone at a little distance; we turned round and beheld the bended form of a female sitting by a newly closed grave. […] She was sitting by the side of the grave with her head supported between her knees but when she heard us approaching and still more when she saw us gazing upon her she smothered her sighs and lifting up her head endeavoured to appear as if tossing about the little crumbling bits of earth with indifference but in doing this it seemed to recal (sic) the idea of what lay beneath and she turned now and then aside for a few moments to weep.

This evocative passage reflects the aesthetics, symbolism and customary behaviour characteristic of a burial ground, whether formal or informal. What is lacking from the Prestwich Memorial is any hint of the dead or funerary symbolism. The information provided on the panels is informative, but dense and unstimulating. The remains are locked away in a vault, packed in cardboard boxes with reference numbers and stored on rows of shelves. Despite the oblique hint of a cemetery wall on its exterior, the space looks and feels like a tidy, blank canvas.

THE LIVING AND THE DEAD

In 2010, Xolelwa Kashe-Katiya (former Deputy Director of the Archival Platform) lamented the limited research access to the remains to learn more about who they were. She attributes this partly to the Western Cape province’s unwillingness to engage with descendents on uncomfortable questions around land reform and restitution. She also pointed to the lack of an enabling policy framework for the treatment of human remains as objects of heritage.

After a decade of discussions, the National Policy on the Repatriation and Restitution of Human Remains and Heritage Objects was finally approved by Cabinet on 16 March 2021, but has yet to move into implementation due to budget restraints. The policy’s scope extends to the repatriation of human remains within South Africa, from outside of South Africa (including military veterans) and from within South African museum collections. It also includes the repatriation and restitution of other heritage objects. To respond to the requests for repatriation and restitution that have already been made to government, the current ask from the National Treasury amounts to R30.66-million. These funds may be used for inventory and provenance research on objects or remains, travel to view and/ or accompany remains or objects to their final destination (by consultants, members of parliament, community members or descendants), as well as preparation and dispatch of the remains or objects. The policy also outlines restrictions on displaying, exhibiting or photographing/ filming physical remains, and lists the agencies responsible for providing permission for access to remains for analysis. Some community groups have unofficially claimed the remains at Prestwich Memorial as their own and insist that they should not be disturbed any further. With the implementation of the policy, it remains to be seen whether researchers will finally gain access 20-years after their discovery.

In 2011, TRUTH Coffee Roasting, a luxury coffee brand, opened a branch at the Prestwich Memorial, occupying almost two-thirds of the interior floor space. The café’s signage features prominently on the building’s multiple facades and Google Reviews for the memorial often make mention of the coffee and food as well. In some cases, the reviews mention only the coffee shop’s menu items or facilities, completely missing the fact that the building is also a heritage site.

In the same year, Jade Gibson (artist and Doctor of Visual Anthropology, University of Cape Town) inserted a life-size skeletal figure made out of twigs and branches into multiple spaces across the city. Pointing to the past inevitably means encountering things, people and places that are no more, but in contemporary South Africa there is a constant, active process to reflect on the absence of certain narratives of individual and public history. Gibson’s trajectory across the city included a stop at Prestwich Memorial, where the skeleton took a coffee break before continuing on its way. This darkly humorous visit points to a few of the site’s deficiencies as an ossuary and site of remembrance. Although only passing through, Gibson’s skeleton is the only visible memento mori on-site, and the indulgence of a cup of coffee is intentionally ironic, given the legacy of the global coffee trade that is linked to colonialism and slavery. The skeleton’s road trip across the peninsula was photographed and filmed to produce a work of video art, titled Rootless. The work was included in the 2011 edition of the Institute for Creative Arts’ city-wide festival, Infecting the City.

DRAWING A COMPARISON

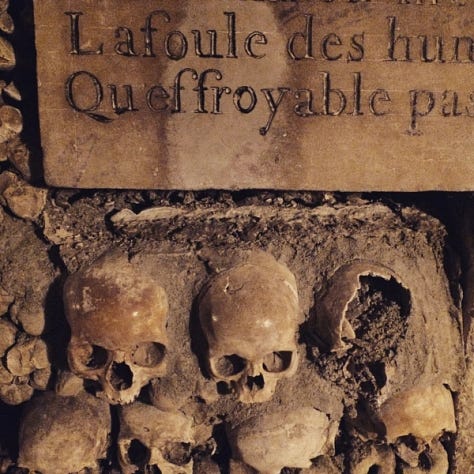

To explore what an ossuary can be, we can compare Prestwich Memorial to one of the largest and best known ossuaries internationally: the Catacombes de Paris. The Catacombes houses the remains of nearly 6-million Parisians. By the late 1700s, burial space in the metropolitan area had reached capacity. Bodies interred in municipal graveyards were overflowing from mass graves and beginning to infect their living neighbours. In response to this, the city designated underground quarry tunnels for a mass reburial to alleviate the problem. In total, 17 cemeteries, 160 religious sites and 145 convents/ monasteries were vacated. The remains were transferred across the city by workmen accompanied by priests in evening processions. In the ossuary, plaques were mounted to show where the bones had come from and when they were transferred. And around these plaques, bones of all kinds were arranged in a decoratively macabre fashion - rows of skulls and mounds of femurs.

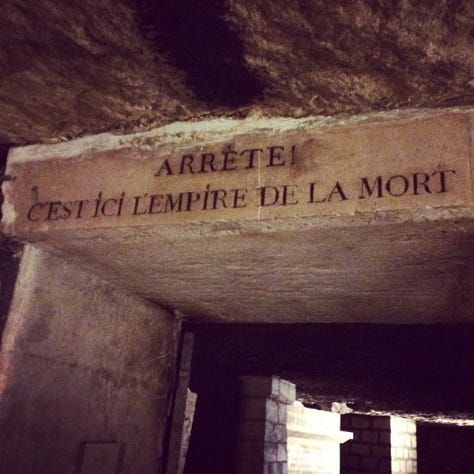

The tunnels were consecrated in 1786 and were opened to the public from 1809. Originally named the ‘Paris Municipal Ossuary’, the site soon became known as the Catacombes de Paris after the Roman catacombs that had captured French imaginations. From the very first, the halls were articulated to the public as something curious and entertaining to behold. In order to get to the ossuary itself, there is almost a kilometre of crude subterranean tunnel to walk through from the entrance at Place Denfert Rochereau. When visitors reach the entrance, the threshold is marked with ominous warnings such as ‘Arrete! C’est ici l’empire de la mort’ (Stop! This is the empire of the dead) and ‘De quelque coté que tu tournes la mort est aux aguets’ (Whichever way you turn death is lurking). Further memento moris (in the form of plaques) are inserted at regular intervals to dramatise the experience, and bone arrangements manage to be both sombre and outrageous.

In a historically Catholic country, the Catacombes are in keeping with French cultural mores. Catholic churches proudly display the physical remains of religious martyrs and devoted members of the church as relics, especially those that appear to be incorruptible (dry and leathery, but not showing other signs of decay or corruption). As the space is decisively consigned to the realm of heritage (displaying objects rather than subjects) and linked to a discrete time of rapid urban development, visitors are not expected to consider whether their own remains may be disturbed in a similar way some day in the distant future.

NO CONCLUSION

The French approach to the relocation and commodification of human remains reflects the attitude of an enormous, impersonal city where new generations need space to make their own meaning and significance. Given South Africa’s fractured history and diverse cultural and religious communities, it is unlikely that the Prestwich Memorial could put the remains found at Prestwich Street on permanent display to the public. This would be a divisive and distasteful choice, especially in light of many of South Africa’s anatomical collections coming under increasing scrutiny. That being said, the memorial would benefit from a more direct engagement with its status as an ossuary and with the overt inclusion of funerary symbols, objects or rituals to mark it as a burial place.

Saidiya Hartman (writer and academic) writes that recovering the stories of figures who have been left out of the historical narratives “has as its prerequisites the embrace of likely failure and the readiness to accept the ongoing, unfinished and provisional character of this effort, particularly when the arrangements of power occlude the very object that we desire to rescue.” In Gibson’s work, and hopefully more like it, we have a better chance of bringing this incomplete history and lethargic memorial to life for the public. Unlike historical records that are sealed documents of the past, art proposes a continuation of historical moments by pulling them into the present in meaningful ways. Art and cultural production offer an invitation to complex stories, subjective experience and increased knowledge in a way that the realm of history and heritage (certain, quantifiable) finds difficult to achieve on its own.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments. 💀

* The panels feature titles like ‘About the Exhibition’, ‘The Stories of District One’, ‘A Site Associated with Slavery’, ‘St. Andrews Church’, ‘Hospitals in District Six’, ‘The People and Their Burials’ and ‘The Architect’s Perspective. The pull up banners outline subjects like ‘Natural Heritage Resources’ and ‘Why is Remembering Important?’

Sources

Memorial honours Cape slaves. Lucille Davie, for The Heritage Portal. https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/memorial-honours-cape-slaves

Green Point dig stopped after remains found. Jason Warner, for IOL.co.za. https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/green-point-dig-stopped-after-remains-found-670718

Prestwich Place Memorial: the treatment of human remains. Beáta America, for the Centre for Curating the Archive (UCT). https://humanities.uct.ac.za/cca/articles/2019-07-02-prestwich-place-memorial

Prestwich Place Memorial: Human remains, development and truth. Xolelwa Kashe-Katiya, for the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative (UCT). https://humanities.uct.ac.za/apc/prestwich-place-memorial-human-remains-development-and-truth

Notes for a Guide to the Ossuary. Green, Louise & Murray, Noeleen. (2009). African Studies. 68. 370-386. doi.org/10.1080/00020180903381230

Gestures of Gratitude // Catharina “Groote Catrijn” Van Paliacatta. Nkgopoleng Moloi, for the Archive of Forgetfulness. https://archiveofforgetfulness.com/Nkgopoleng-Moloi

PRESTWICH MEMORIAL: Ossuary, memorial garden & visitor centre. City of Cape Town. https://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/Graphics%20and%20educational%20material/Heritage_The_Prestwich_Memorial_2015-12.pdf

Prestwich Memorial Ossuary and Old Tram Tracks CT. KNewman1, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prestwich_Memorial_Ossuary_and_Old_Tram_Tracks_CT.jpg

Draft National Policy on the Repatriation and Restitution of Human Remains and Heritage Objects. Department: Arts and Culture. Republic of South Africa. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/cultural-affairs-sport/draft_national_policy_on_the_repatriation_and_restitution_of_human_remains_and_heritage_objects.pdf

Repatriation & Restitution Policy of Human Remains & Heritage Objects; Covid-19 Relief Fund 3rd phase; with Minister. Parliamentary Monitoring Group. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33319/

Walks and Sketches at the Cape of Good Hope. Robert Semple. (1805). London: C. and R. Baldwin, New Bridge- Street. Google Books result: https://books.google.nl/books?id=g25CAAAAcAAJ&hl=nl&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Coffee gives the spirits a lift. Brent Meersman, for Mail & Guardian. (15 April 2011). https://mg.co.za/article/2011-04-15-coffee-gives-the-spirits-a-lift/

Skeletal (in-)visibilities in the city – Rootless : a video sculptural response to the disconnected in Cape Town. Jade Gibson. (2013). South African Theatre Journal 26(2). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272123509_Skeletal_in-visibilities_in_the_city_-_Rootless_a_video_sculptural_response_to_the_disconnected_in_Cape_Town

Les Catacombes de Paris. https://www.catacombes.paris.fr/en

L’insolite histoire des Catacombes de Paris. Antoine Vitek, for Culturez Vous. https://culturezvous.com/en/history-paris-catacombs/

Venus in Two Acts. Saidiya Hartman. (2008). Small Axe, Number 26 (Volume 12, Number 2). https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/research/centres/blackstudies/venus_in_two_acts.pdf